The Marketplace in Your Brain

Neuroscientists have found brain cells that compute value. Why are economists ignoring them?

Lauren Lancaster for The Chronicle Review

Screens show an experiment and results from a functional-magnetic-resonance-imaging machine in the lab at the Center for Neuroeconomics at New York U. Elizabeth Phelps, the psychologist running this project, says that she was "initially skeptical" that economics could refine neuroscience but that she has become a convert.

In 2003, amid the coastal greenery of the Winnetu Oceanside Resort, on Martha's Vineyard, a group of about 20 scholars gathered to kick-start a new discipline. They fell, broadly, into two groups: neuroscientists and economists. What they came to talk about was a collaboration between the two fields, which a few researchers had started to call "neuroeconomics." Insights about brain anatomy, combined with economic models of neurons in action, could produce new insights into how people make decisions about money and life.

A photo taken during one of those sun-dappled days captures the group posed and smiling around a giant chess set on the resort lawn. Pawns were about two feet tall, kings and queens about four feet. Informally, the neuroscientists began to play the black pieces. The economists began to play white.

Today, nearly a decade later, a few black pawns have moved down the board. But the white pieces have stayed put. "I would say that neuroeconomics is about 90 percent neuroscience and 10 percent economists," says Colin F. Camerer, a professor of behavioral finance and economics at the California Institute of Technology and one of the prime movers in the new field. "We've taken a lot of mathematical models from economics to help describe what we see happening in the brain. But economists have been a lot slower to use any of our ideas."

On Camerer's side, there has been a good deal of action. Neuroeconomics came into being around the turn of this century, growing out of a critique of the basic idea in economics that people are driven by rational attempts to maximize their own happiness. A new breed of behavioral economists had noted that in reality, individual definitions of "maximize" and "happiness" seemed to vary. Neuroeconomists added the idea that, by mapping parts of the brain doing the maximizing and the happiness-defining, they could better account for those actions.

Through experiments, researchers have shown that when people reject a low, unfairly priced offer, a part of the brain associated with disgust kicks in, but that when they view the offer as fair, a brain region linked to reasoning seems more active. Researchers have also tackled the puzzle of "overbidding," when people pay too much for something. An area called the striatum, associated with rewards, is more active when people bid high in an auction because they fear losing an item, but is not as active when they think they have a good chance of winning. So fear of losing may be key to things like overvalued stocks.

Other research has shown that decisions to be very social and involved with a group, rather than hang on the fringes, may be linked to an especially active gene for dopamine, a neurotransmitter—and that the social tendency may be inherited.

This week hundreds of neuroeconomists will convene for their annual meeting to hear more about this kind of work, a mark of how far the field has come since that tiny gathering on Martha's Vineyard. They have secured millions of dollars in research financing from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. Their papers are regularly published in leading journals like Nature andScience.

Yet economists for the most part have not been moved. Two of them, Princeton University's Faruk Gul and Wolfgang Pesendorfer, argued in a paper called "The Case for Mindless Economics" that the discipline has been doing just fine by ignoring brain activity and looking only at results. David K. Levine, a professor of economics at Washington University in St. Louis, puts it more starkly: "Look, if you are trying to understand a pilot's ability to land a crippled plane, it's not the patterns of his neuron firing that's important. It's the experience and training that he's had, and the result of the landing. Neuroeconomics hasn't offered anything that can improve on those measures."

This is not exactly the confluence dreamed of by the chess players. One of them, Paul W. Glimcher, director of the Center for Neuroeconomics at New York University and author of the standard textbook in the field, wrote in a 2004 paper published inScience that "economics, psychology, and neuroscience are converging today into a single, unified discipline." Today he is more measured. "We are a very young science," he says, "and we've taken more from economics than we've given. I hope in the coming years you'll start to see us give more back."

And economics does need some help, according to a few practitioners like the eminent Yale University economist Robert J. Shiller, who has argued that the discipline isn't doing just fine. Most economic models didn't predict the 2008 housing crash, he pointed out in a speech at last year's Society of Neuroscience meeting. Adding some understanding of how the brain reacts to particular kinds of uncertainties or ambiguities in supply and demand, he said, might avoid this and other costly misfires.

Camerer, who was trained in economics—he got an M.B.A. and a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago and "didn't know anything about neuroscience until 2000"—says that assuming that economics can't be improved by knowing how the brain computes value might be the most unsound prediction of all. "That's really kind of a crazy bet," he says.

Neuroscience and psychology could also do with improvement, and that's where economics comes in, says Elizabeth A. Phelps. "I was initially skeptical," says Phelps, a psychologist who runs a lab at the NYU neuroeconomics center. "But the more I saw of the mathematics and its ability to tease apart and model components of complex behavior, the more I realized that psychology hadn't been very good at that. Economics had ways to represent theories of behavior"—the brains of people making certain choices will react in certain ways—"and this allowed us to test those theories in a rigorous way."

Probably the easiest way to understand how neuroeconomics might contribute to all these disciplines is to look at a few experiments. One recent study, published this summer, searched for brain regions associated with altruism and selfishness. Ernst Fehr, a professor of economics at the University of Zurich, and one of the few economists working extensively with neuroscientists, asked a group of 30 men and women to split a sum of money with another person or keep more for themselves. While each person was making the decision, Fehr's team took images of his or her brain in a functional-magnetic-resonance-imaging machine. The fMRI scanner reveals fine details of brain anatomy and, crucially, measures how active brain regions are. It has become a standard tool in this field.

Those people who were willing to split more money had more neurons in a region called the right temporo-parietal junction, an area toward the back of the brain that has been linked to empathy. Selfish people had a smaller junction. Moreover, the junction became more active as unselfish people decided to give more money away, Fehr and his colleagues found. It is almost as if the region worked hardest when people were trying to overcome what might be a natural—and rational—impulse toward selfishness.

Giving people ultimatums reveals more detail about competition among brain regions that do different things. Ultimatum games pit greed against justice, and neuroeconomists like to put people in these dilemmas. Suppose your friend has $10, and she can split it with you any way she wants. The catch is that if you reject her offer, you both get nothing. If you are both rational, she will offer you a low amount, maybe even $1. That way she gets to keep $9 if you accept, which you would certainly do because $1 is better than nothing.

Of course, that's usually not what happens. Low offers get rejected; there seems to be an impulse to punish stinginess even at the expense of personal gain. Jonathan D. Cohen, a neuroscientist at Princeton, went looking for the seat of that impulse. He asked 19 people to play ultimatum games with stingy offers. Two areas of the brain were active when people considered what to do. One, near the front of the brain, is called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and is linked to deliberative thought and calculation. The other, deeper in the brain, is tied to emotions like disgust. It's called the insula. The stingier the offer, the more insula activity Cohen's team saw. When people actually rejected the offer, this activity peaked higher than did activity in the deliberative-thought area. It appears, Cohen says, that two areas are competing in some way, and that negative emotions—or the desire for justice—can trump people's rational desire to get more.

Phelps, at NYU, has used another kind of competition, bidding in an auction, to cast doubt on a standard economic and psychological explanation for placing too much value on things: stocks, houses, or products on late-night infomercials. That explanation usually centers on the rush you get from success, or "the joy of winning." The psychologist, whose office sits eight stories above an fMRI machine purchased specifically for neuroeconomics and related studies, collaborated with an NYU economist, Andrew Schotter, to show that winning may be the last thing on people's minds.

The researchers had 17 people lie in the fMRI and play many rounds of a lottery, where winning was out of their control, and join many auctions, in which they could control the outcome because they had to bid against a partner. In the auctions, but not the lottery, people showed exaggerated activity in the striatum, deep in the brain, which reacts to unpleasant sensations as well as rewards. The more activity, the greater the tendency to overbid.

This was a bit of a puzzle, Phelps says, so she and her colleagues designed a refinement on the auction. Now people were told they would be penalized $15 if they didn't win. At other times there was no penalty. With the consequences of losing front and center, people consistently bid much higher than they did in regular auctions. "It wasn't the joy of winning that pushed them," says Phelps. "It seemed more like fear of losing, because it only happened when we told them that losing at the auction could cost them. It wasn't something that standard economic theory would predict."

Michael L. Platt, director of the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, has taken neuroeconomics down to the genetics level. "We want to see if tendencies to make certain decisions are not only the brain reacting to particular situations, but also might be inherited," he says. He and his team have collected data on 1,500 to 2,000 adults as they run through various decision-making tasks. The scientists are analyzing the subjects' DNA for variations in genes that produce neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin, communications agents between many of the brain regions highlighted in the other neuroeconomics experiments.

In monkeys, the genes do seem to make a difference. Platt has been monitoring a colony of macaques that live on an island off the coast of Puerto Rico. The animals are highly social, but some are more so: Regardless of social status in the monkey group, some take actions to put themselves at the center of things, while others hang back. The Duke team has found that the more social ones have a different version of the gene controlling serotonin function. And their offspring make the same choices and have the same gene. "What we are seeing is that decision tendencies are heritable," Platt says.

Those findings are not bulletproof. One persistent critique of brain-scanning experiments is that while scans show activity in a region, it's hard to tell if that activity is exciting or inhibiting decision-related nerve impulses. So its exact role in a decision is difficult to pin down. And while there are hints that the scans can predict behavior, that hasn't been shown in a robust way. One study, by Gregory S. Berns, a professor of economics at Emory University who was trained as a psychiatrist, did show that brain activity in teenagers listening to specific music foretold a small increase in national sales of particular albums. The effect was limited but real, Dr. Berns notes.

Still, this early work has attracted a fair amount of money. Making sense of seemingly irrational decisions has implications for understanding why people do things that are bad for them, like taking drugs or overeating. That has caught the attention of the National Institutes of Health, which finances 21 current research projects with "neuroeconomics" in their descriptions, to the tune of $7.6-million. The agency gives out many more millions for other neurobiology work related to decision-making: Caltech got $9-million this month to establish a center in this field. The National Science Foundation has backed eight neuroeconomics projects with $3.5-million in research money.

Much of the NIH money comes from its institutes for drug addiction, mental health, and aging. "Most of us, to get funding, have to sell our ideas along disease lines," says Phelps. "Drug addiction is an obvious area where understanding reward-seeking behavior is important, and our work is clearly related to that."

The NIH wants to know more about choices because it's clear that many people understand what's needed to stay healthy but choose not to do it, says Lisbeth Nielsen, chief of the branch of individual and behavioral processes at the National Institute on Aging. "We're very interested in decision-making and aging," she says. "And that's not just health decisions but choices about insurance plans or how to manage your retirement savings. Are changes in choices related to the underlying neurophysiology? Or is it the environment? You won't know unless you get input from different sciences, and that's what neuroeconomics brings to us."

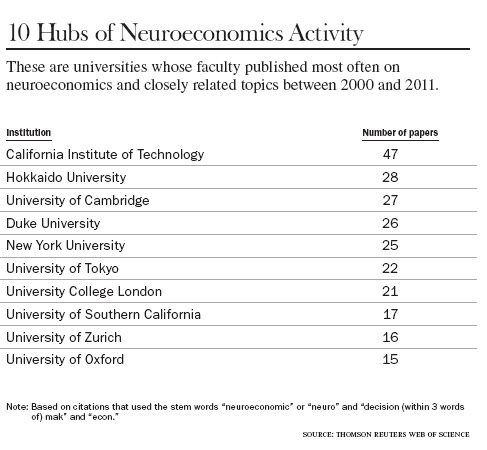

The money is only one measure of how far the field has come. Universities such as NYU, Caltech, Duke, and Zurich have added research centers in the field during recent years, and papers regularly come out of a host of other institutions (see table). This fall Maastricht University, in the Netherlands, inaugurated the first master's degree specific to the field. And at the end of this month, when the Society for Neuroeconomics holds its annual meeting, in Miami, the group will boast 247 members. It started with 84 members in 2004. There will be a few broad-ranging presentations—"A Neuroeconomic Theory of Self-Control"—and many narrow ones—"Ventromedial prefrontal cortex and decisions to sustain delay of gratification"—that delve deeply into the details of the brain.

"For us it's kind of a sanctuary," says Caltech's Camerer. "There are no economists there complaining that this isn't really economics. It's a very bottom-up meeting."

Still, everyone knows those complaints exist. "I do worry that economists have kind of dropped out of the discussions," says Phelps. "This might become 'decision neuroscience' rather than neuroeconomics."

An analysis of cross-citations by The Chronicle and the Eigenfactor Project, at the University of Washington, shows that the picture isn't all bleak. While journals in neuroscience and economics were not citing each other at all in 1997, just before the early neuroeconomics papers were published, by 2010 they were talking back and forth.

But an analysis of mainstream economics journals by Clement Levallois, a researcher at Erasmus University Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, is more pessimistic. He found about 200 articles, published over a recent 10-year period, that mentioned concepts in neuroscience or biology. But the terms they focused on were concepts like "genetics," rarely anything strongly tied to neuroeconomics, like specific parts of neuroanatomy that have been linked to decision-making, or words like "dopamine."

The reluctance isn't surprising, says Michael Woodford, a noted monetary theorist and professor of economics at Columbia University. "Economics is a field where there is a core of ideas developed during the 19th and 20th centuries that people agree are important," he says. "If you want to argue that something should be part of that core, the bar is going to be higher than in many other fields." For neuroeconomics, he adds, "that's a promise that has yet to be delivered on."

That's from someone who is beginning to use neuroeconomics in his own research. Woodford studies how people rank alternatives when making choices. So he has become very interested in perception—what information the brain gets about those choices. "That's the first step, happening before a decision is made," he says. "I'm trying to build mathematics into models that accounts for variance in people's perceptions." He's actually working on ways that backgrounds affect perceptions of brightness, but the principle could apply to how some people focus on the nicely sized bedrooms of a house that's for sale, for instance, while others fixate on its tiny yard. "Standard economic theory treats these things as anomalies, and we shrug it off. But what if we treated these as phenomena that help make sense of these choices?"

The only way to find out, he says, is to do it. And if it works, if a model of a mental process improves an economist's ability to predict what people will do, "then I think neuroeconomics could be very big."

Josh Fischman is a senior writer at The Chronicle.

Correction (9/25/2012): This article was changed to clarify that Gregory Berns believes the predictive effects of brain scans are small but real, and has done experiments to demonstrate this.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario